Optimizing React: Part 1 - Understanding Renders

Table of Contents

This is the first article in a series covering techniques for optimizing React's performance by minimizing renders.

- Part 1 - Understanding Renders (this post)

- Part 2 - Understanding Memoization

- Part 3 - Avoiding Memoization

In my experience, React's memoization functions have been a source of confusion for many developers - either being criminally overused in the name of "performance", or woefully underutilized.

In this series, I'm going to attempt to dispel the uncertainty of when to use these functions, understand their trade-offs, and introduce you to ways of avoiding them altogether.

So what is Memoization? It's a technique where the result of an expensive computation is cached to improve performance on subsequent calls to it. It's a trade-off that consumes more memory to save on execution time.

In React, its memoization functions are primarily used to:

- Avoid unnecessary re-renders of a component (using

React.memo) or re-execution of expensive logic (usinguseMemoor state initializers). - Provide a stable reference for objects (both

useMemoanduseCallback).

Devs tend to focus on the first point - where some overuse those functions in the name of "performance". But point number 2 is an important use case for React's functional components, especially when writing libraries, and is often overlooked.

To really understand in which circumstances we make use of them, I need to cover the basics of how React works - apologies to those who are already familiar with this, but it's useful that everyone is on the same page with the terminology used here.

An overview of React

For simplicity, I'm going to pretend React classes don't exist.

React provides us with a component based abstraction for easily updating the DOM in response to state changes. This is done by representing the DOM with a Virtual DOM (V-DOM), that is nothing more than a lightweight representation of the actual DOM.

In other words, the V-DOM is just a collection of simple Javascript objects used to represent the actual DOM.

The idea behind this is that since updates to the actual DOM are expensive operations, we could instead make frequent updates to the V-DOM, and then figure out which of the actual DOM elements need to be updated.

This process of finding the difference between the previous and next V-DOM state is called reconciliation. Reconciliation is fast but does not aim to be very accurate - just good enough to minimize unnecessary updates to the actual DOM for most practical use cases.

With that out of the way, time for some terminology:

- A React Element is a simple Javascript object that represents a node in the V-DOM.

- A React Component is a function that accepts some props and returns React Elements.

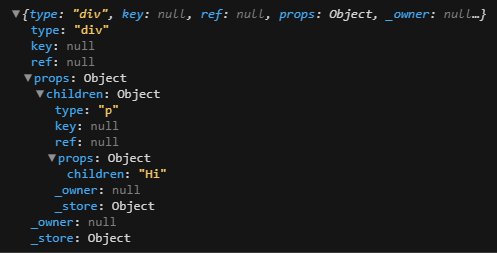

This is what a React element looks like, and you can get this by just console logging the output of a component:

- A render is when the React Component (i.e. the function) is executed.

- A commit is when React actually updates a DOM element.

Note the difference between render and commit. Many developers confuse the two, but they are not the same. When a component "renders", it does not necessarily mean the DOM is going to be updated - React may have figured out that nothing has changed after a state update, and skip updating portions of the DOM.

To really drive home this point, React components can render many, many times. These are just basic functions being executed after all - and in most cases, they execute fast with minimal impact on performance. It's objects like the one pictured above that get updated every render - based on how they change, React will decide which DOM elements to update.

Understanding what happens in a render

Here are some possible reasons a component would re-render (this list is not exhaustive):

- The component's parent has re-rendered.

- The component's state changed (i.e.

setStatewas called). - The component is a subscriber to a React Context - every time the Context value changes, the component will re-render.

Understanding why your component has re-rendered is a critical first step in diagnosing React performance problems. As an exercise, see if you could identify what would cause the example component below to re-render:

function Counter() { const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0); const user = useContext(UserContext); // A callback to increment the counter, passed to FancyButton const incrementer = () => { setCounter((prev) => prev + 1); }; // An object that is the prop to FancyButton // I'm aware this is a little unusual, but there are situations where // you pass in complex objects as props to a component. const buttonConfig = { name: "hello", display: counter, }; return ( <div> <h3>My Special Counter</h3> <p>Hello, {user}!</p> <FancyButton config={buttonConfig} onClick={incrementer} /> </div> ); }

The following are triggers that would cause Counter to re-render:

- The parent of

Counteris re-rendered. setCounteris called via theincrementercallback (and it's called with a different value - React has an optimization where if the new value tosetStateis the same as the old, a re-render will not happen).- The object returned by

useContexthas changed.

Every time one of the above triggers are set off, React will execute the Counter function again, and return the child elements.

These child elements, written as JSX, are nothing more than functions too - they are compiled into React.createElement(args) function calls.

The reason why we use JSX is that it provides a nice familiar declarative abstraction like HTML to write our components - just imagine writing a page as a bunch of nested function calls!

Below is an example of what React code (before v17.0) would transform to (taken from the Babel React Transform Plugin docs):

const profile = React.createElement( "div", null, React.createElement("img", { src: "avatar.png", className: "profile" }), React.createElement("h3", null, [user.firstName, user.lastName].join(" ")) );

So continuing with our example, with each re-render of Counter, the following will happen:

incrementerwill be assigned to a new callback object. Remember functions in Javascript are objects too!buttonConfigwill also be assigned to a new object. Remember that{} !== {}. So bothincrementerandbuttonConfigwill be assigned to new references in memory on every render.- All the React Elements returned from

Counterwill be recreated.

Now let's discuss performance. Given what we know from above, would repeated renders of Counter impact performance by constantly re-allocating memory for variables and running all those functions again? Not really.

These operations are quite cheap, and the Javascript runtime is optimized for doing these operations efficiently. But this could be a problem if you have an app with hundreds or thousands of components re-rendering frequently (and of course, it depends on the user's hardware).

So do we wrap everything we can with memo, useMemo and useCallback? Some people do, which is probably why you see a lot of blog posts saying to avoid abusing React's memo functions for optimizing performance - it's because the act of memoization trades off time for space. We cache prior values and return them instead of executing functions again.

But there's a small cost with this. And the cost could be significant if we end up not using the cached values much, and end up frequently caching a value, throwing it away because it's stale, and then creating a new one.

Since it's easy to shoot yourself in the foot and use these incorrectly, premature optimization should be avoided.

However as long as you understand how React works, choosing when to use the memoization functions is pretty straightforward. And in my experience, you don't need to use them too often.

What about effects?

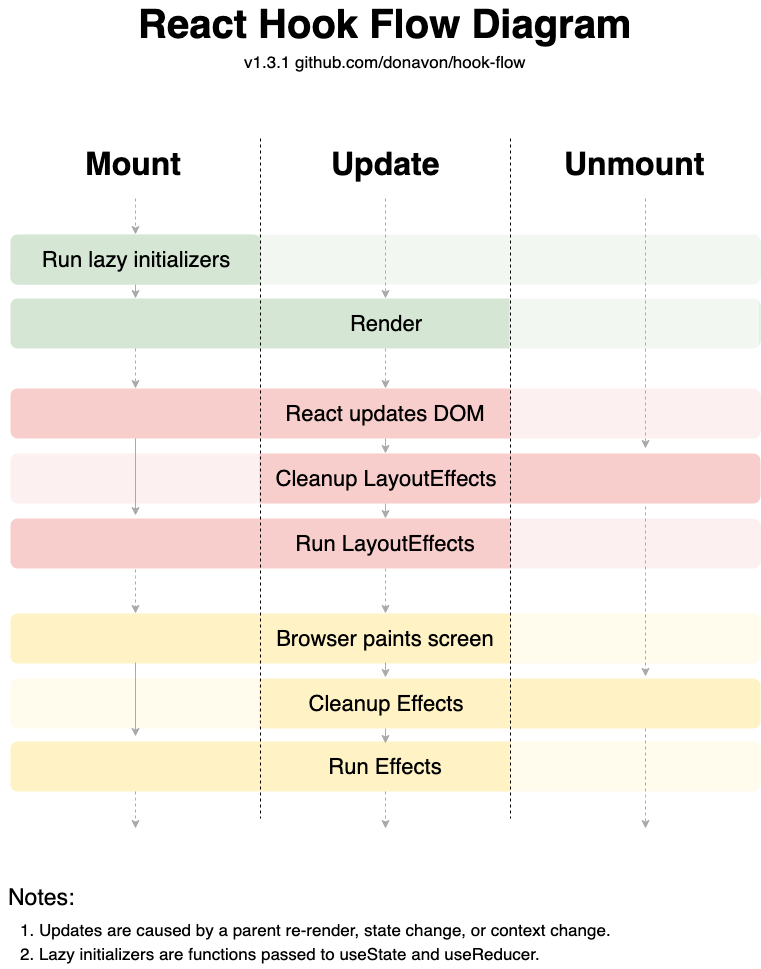

If you now understand what goes on when React renders a component, you may wonder when does useEffect and useLayoutEffect run. Understanding these hooks is beyond the scope of this series, so a short summary of them is:

useLayoutEffectsruns after a render but before the browser paints the DOM (i.e. when you can actually see your changes). It is a synchronous (i.e. blocking) operation.useEffectsruns after the component renders and the browser paints the DOM. It is an asynchronous (non-blocking) operation.

This article by Kent C Dodds, explains when you should prefer one over the other.

And this image by Donavan West visualizes when these hooks run:

To be continued...

Now that we've covered why a component can re-render, and how variables are given new references on each render, we can dive into optimization - which we will do in my next article.